Where do the molecules required for life originate? It may be that small organic molecules first appeared on earth and were later combined into larger molecules, such as proteins and carbohydrates. But a second possibility is that they originated in space, possibly within our solar system. A new study, published this week in the Journal of Chemical Physics, from AIP Publishing, shows that a number of small organic molecules can form in a cold, spacelike environment full of radiation.

Investigators at the University of Sherbrooke in Canada have created simulated space environments in which thin films of ice containing methane and oxygen are irradiated by electron beams. When electrons or other forms of radiation impinge on so-called molecular ices, chemical reactions occur and new molecules are formed. This study used several advanced techniques including electron stimulated desorption (ESD), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and temperature programmed desorption (TPD).

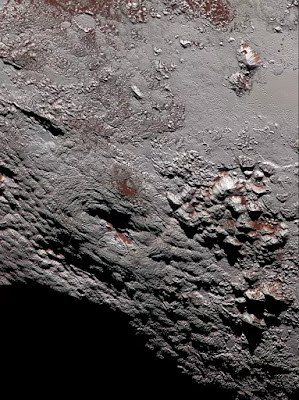

The experiments were carried out under vacuum conditions, which both is required for the analysis techniques employed and mimics the high vacuum condition of outer space. Frozen films containing methane and oxygen used in these experiments further mimic a spacelike environment, since various types of ice (not just frozen water) form around dust grains in the dense and cold molecular clouds that exist in the interstellar medium. These types of icy environments also exist on objects in the solar system, such as comets, asteroids and moons.

All of these icy surfaces in space are subjected to multiple forms of radiation, often in the presence of magnetic fields, which accelerate charged particles from the stellar (solar) wind toward these frozen objects. Previous studies investigated chemical reactions that might occur in space environments through the use of ultraviolet or other types of radiation, but this is a first detailed look at the role of secondary electrons.

Copious amounts of secondary electrons are produced when high-energy radiation, such as X-rays or heavy particles, interact with matter. These electrons, also known as low-energy electrons, or LEES, are still energetic enough to induce further chemistry. The work reported this week investigated LEEs interacting with icy films. Earlier studies by this group considered positively charged reaction products ejected from ices irradiated by LEEs, while the work reported this week extended the study to include ejected negative ions and new molecules that form but remain embedded in the film.

The research group found that a variety of small organic molecules were produced in icy films subjected to LEEs. Propylene, ethane and acetylene were all formed in films of frozen methane. When a frozen mixture of methane and oxygen was irradiated with LEEs, they found direct evidence that ethanol was formed.

Indirect evidence for many other small organic molecules, including methanol, acetic acid and formaldehyde was found. In addition, both X-rays and LEEs produced similar results, although at different rates. Thus, it is possible that life's building blocks might have been made through chemical reactions induced by secondary electrons on icy surfaces in space exposed to any form of ionizing radiation.