Summary:

Like a computer, cells must process information from the outside world before they respond. Scientists have now developed a powerful new way to observe the internal discussions responsible for cellular decisions.

A new imaging technology lets scientists spy on the flurry of messages passed within cells as they do... potentially everything.

Until now, most scientists could visualize only one or two of these intracellular signals at a time, says Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator Ed Boyden of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His team’s new approach could make it possible to see as many signals as you want – in real time, at once, Boyden says – giving researchers a more detailed view of cells’ internal discussions than ever before.

In tests with neurons, the researchers examined five signals involved in processes such as learning and memory, Boyden and his colleagues report November 23, 2020, in the journal Cell. “You could apply this technology to all sorts of biological mysteries,” he says. “Every cell works due to all the signals inside it.” Because signaling contributes to all biological processes, a better means to study it could illuminate a host of diseases, from Alzheimer’s to diabetes and cancer.

The team’s new approach is a breakthrough, says Clifford Woolf, a neurobiologist at Harvard Medical School who was not involved with the work. He plans to use it to examine how pain-sensing neurons become more sensitive in injury or illness. With the new imaging technology, he says “we can take apart what’s happening in cells in a way that just has not been possible before.”

Give a computer or a human brain information, and it will crackle with electrical impulses as it prepares a response. Within cells, these impulses result in spurts of multiple molecular signals. Boyden describes this process as a group conversation. “Signals within a cell are like a set of people trying to decide what to do for the evening: they take into account many possibilities, and then decide what to collectively do,” he says.

These cellular discussions are what prompt, for example, a neuron to encode a memory or a cell to turn cancerous. Despite their importance, scientists still don’t have a strong grasp of how these signals work together to guide a cell’s behavior.

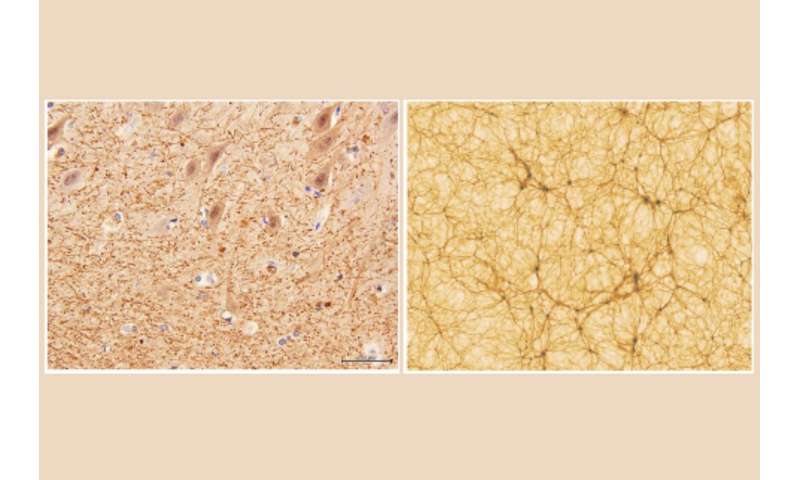

To see cell signaling in action, scientists typically introduce genes encoding sensors connected to fluorescent proteins. These molecular reporters sense a signal and then glow a specific color under the microscope. Researchers can use a different color reporter for each signal to tell the signals apart. But finding sets of reporters with colors that a microscope can differentiate is challenging. And a typical cellular conversation can involve dozens of signals – or more.

Changyang Linghu and Shannon Johnson, scientists in Boyden’s lab, got around this limitation by affixing reporters to small, self-assembling proteins that act like LEGO bricks. These small proteins “clicked together,” forming clusters that were randomly scattered across the cell like little islands. Each cluster, which appears under the microscope as a luminescent dot, reports only one type of cellular signal. “It’s like having some islands with thermometers to report temperature and other islands with barometers measuring pressure,” Johnson says.

In experiments with neurons, the team created clusters that each glowed upon detection of one of five different signals, including calcium ions and other important signaling molecules. After imaging the live cells, the researchers attached molecular labels to the glowing dots to identify the reporters located there. Using computer analyses, the team turned the dots magenta, yellow, and other colors, depending on whether they represented calcium or another signal. This let them see which signals were switching on and off across a cell’s interior.

By monitoring so many signals at once, the team was able to figure out how each signal related to one another. “Teasing apart such relationships could help scientists understand complex processes – like learning, ” Linghu says.

He likens a cell to an orchestra and its signals to a symphony. “It’s difficult to fully appreciate a symphony by listening to just a single instrument,” he says. Because the new technique lets scientists observe multiple signals at the same time, “we can understand the symphony of cellular activities.”

Boyden’s team estimates it may be possible to detect as many as 16 signals with their technology, but improvements in genetic engineering techniques could raise that number significantly. “Potentially, you could look at dozens, hundreds, or even more signals,” he says. “The next challenge,” Boyden says, “is getting sensors for all of those signals into a cell.”