“As we move out, we see continuously from our planet all the way out into the realm of galaxies in a light-travel time, giving you a sense of how far away we are. As we move out, the light from these distant galaxies have taken so long, we’re essentially backing up into the past. We back so far up we’re finally seeing a containment around us the afterglow of the Big Bang,” says Carter Emmart, one of the creators of the Digital Universe.

A recently discovered galaxy is undergoing an extraordinary boom of stellar construction, revealed by a group of astronomers led by University of Florida graduate student Jingzhe Ma using NASA’s Chandra X-Ray Observatory.

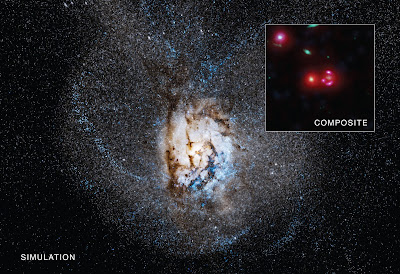

The galaxy known as SPT 0346‐52 is 12.7 billion light years from Earth, seen at a critical stage in the evolution of galaxies about a billion years after the Big Bang Seed.

Astronomers first discovered SPT 0346‐52 with the National Science Foundation’s South Pole Telescope, then observed it with space and ground-based telescopes. Data from the NSF/ESO Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array in Chile revealed extremely bright infrared emission, suggesting that the galaxy is undergoing a tremendous burst of star birth.

However, an alternative explanation remained: Was much of the infrared emission instead caused by a rapidly growing supermassive black hole at the galaxy’s center? Gas falling towards the black hole would become much hotter and brighter, causing surrounding dust and gas to glow in infrared light. To explore this possibility, researchers used NASA’s Chandra X‐ray Observatory and CSIRO’s Australia Telescope Compact Array, a radio telescope.

No X‐rays or radio waves were detected, so astronomers were able to rule out a black hole being responsible for most of the bright infrared light.

“We now know that this galaxy doesn’t have a gorging black hole, but instead is shining brightly with the light from newborn stars,” Ma said. “This gives us information about how galaxies and the stars within them evolve during some of the earliest times in the universe.”

Stars are forming at a rate of about 4,500 times the mass of the Sun every year in SPT0346-52, one of the highest rates seen in a galaxy. This is in contrast to a galaxy like the Milky Way that only forms about one solar mass of new stars per year.

“Astronomers call galaxies with lots of star formation ‘starburst’ galaxies,” said UF astronomy professor Anthony Gonzalez, who co-authored the study. “That term doesn’t seem to do this galaxy justice, so we are calling it a ‘hyper-starburst’ galaxy.”

The high rate of star formation implies that a large reservoir of cool gas in the galaxy is being converted into stars with unusually high efficiency.

Astronomers hope that by studying more galaxies like SPT0346‐52 they will learn more about the formation and growth of massive galaxies and the supermassive black holes at their centers.

“For decades, astronomers have known that supermassive black holes and the stars in their host galaxies grow together,” said co-author Joaquin Vieira of the University of Illinois at Urbana‐Champaign. “Exactly why they do this is still a mystery. SPT0346-52 is interesting because we have observed an incredible burst of stars forming, and yet found no evidence for a growing supermassive black hole. We would really like to study this galaxy in greater detail and understand what triggered the star formation and how that affects the growth of the black hole.”

SPT0346‐52 is part of a population of strong gravitationally-lensed galaxies discovered with the SPT. It appears about six times brighter than it would without gravitational lensing, which enables astronomers to see more details than would otherwise be possible.

A paper describing the results appears in a recent issue of The Astrophysical Journal and is available online. NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, manages the Chandra program for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts, controls Chandra’s science and flight operations.